Tra le 5.000 fotografie realizzate da Laura Grisi dalla fine degli anni Cinquanta alla fine degli anni Sessanta, durante i lunghi viaggi compiuti accanto al marito documentarista Folco Quilici, probabilmente è nascosto il segno della sua insofferenza verso la presunta fedeltà al reale attribuita al mezzo fotografico.

Tra gli scatti ce n’è uno in particolare che, come in un rebus, anticipa i temi della sua ricerca artistica a partire dal presupposto che nella fotografia, soprattutto documentaria, non si è mai inclusi come soggetti se non nell’esercizio di un potere che è il privilegio di uno sguardo etnocentrico.

La foto è intitolata A nomad and “his mosque” (a stone square in the desert)1 e mostra un uomo nel deserto dell’Arabia Saudita, girato di spalle nell’atto di incamminarsi verso l’orizzonte, ai cui piedi vi è una forma rettangolare circoscritta da pietre irregolari, di misura maggiore ai quattro vertici. La vicinanza e l’atteggiamento dell’uomo accanto a quel perimetro fanno pensare a un primitivo atto di delimitazione di uno spazio, seguito dal suo abbandono.

Questa scena, contestualizzata nel percorso artistico compiuto da Laura Grisi, si presta a una lettura più profonda. Quel rettangolo sembra simulare la geometria della cornice e quindi uno spazio assegnato alla rappresentazione, incontrastato topos della tradizione modernista, ulteriormente definito perché inserito a sua volta dentro il riquadro della fotografia e in quanto «moschea» – come indicato dal titolo – connotato anche come «sacro». Il nomade se ne distacca dopo averlo predisposto, così come l’artista che, dopo averlo fotografato, si separerà sia dall’immagine per passare a quella successiva che, in seguito, da quella tipologia di ripresa perché disillusa dal risultato.

Resta un ultimo elemento, il deserto, dove quel «soggetto nomade»2 si sposta, decifra e seppellisce le tracce del suo passaggio facendo risuonare, così, l’idea di infinito e di mutamento, ancora qualcosa di vicino allo spazio invisibile del «sacro» segnalato dalla «moschea».

A nomad and “his mosque” è, dunque, un’immagine che già delinea, per il significato di questi contenuti, il rapporto che l’artista instaurerà con la dimensione dell’immaterialità, necessaria a causa della consapevolezza acquisita rispetto alla parzialità dei metodi di rappresentazione nella traducibilità del reale.

Questo è anche uno dei temi sviluppati dalla recente retrospettiva a lei dedicata presso il Muzeum Susch, curata da Marco Scotini.3 La mostra indaga, infatti, come la resa obiettiva della realtà attribuita alla fotografia, nella ricerca di Grisi, pur restando sempre sottotraccia, sia letteralmente smontata e ripresentata nei lavori realizzati tra gli anni Sessanta e Settanta nell’unica via possibile: una sua riformulazione concettuale e performativa in cui «non sarà più la singola immagine ad avere importanza ma il modo con cui essa si rapporta ad ogni altra come un caso del possibile».4

Tra il 1965 e il 1966 il percorso intrapreso da Laura Grisi inizia a prendere le distanze dalla rappresentazione pittorica per constatare il dissolvimento di un’idea univoca di centro, spazio, tempo e identità.

Le opere presentate presso la Galleria dell’Ariete di Milano nel 1965 segnano, infatti, il passaggio a una pittura dove in questo caso l’oggetto principale è un esame dettagliato del funzionamento del medium fotografico. Il piano pittorico diventa una sorta di «tavola anatomica»5 in cui frammenti di paesaggio si combinano a calcoli e schemi su ottiche, lenti e gradi di apertura dei diaframmi che nelle successive Pitture Variabili lasceranno il posto a un elemento di dinamicità: un sistema di pannelli scorrevoli che slittano sulla superficie del quadro, permettendo così alle immagini di sovrapporsi e cambiare inquadratura, per un coinvolgimento dell’osservatore.

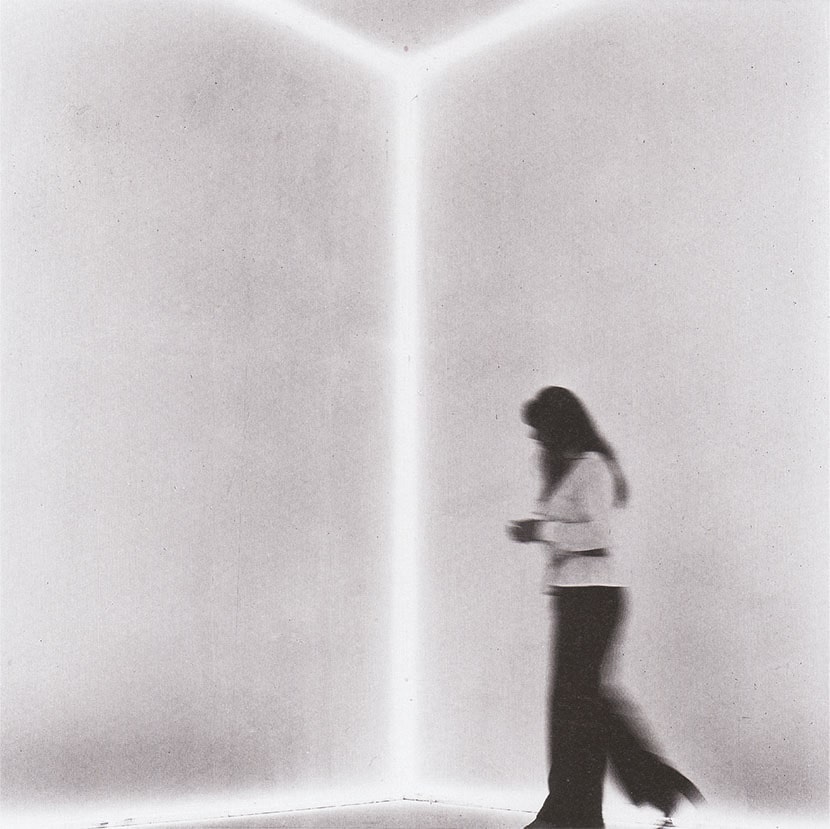

In entrambe le serie lo spazio pittorico è quasi sempre occupato dalla silhouette monocromatica dell’artista dentro l’impaginato della composizione ma, nei Variabili, è sottratta alle diverse combinazioni delle parti scorrevoli. Spettatrice o autrice, questo soggetto-ombra è «frammento» ma anche «ambasciatore della realtà all’interno del quadro»6 e richiama in sé l’«immagine di una temporalità ambivalente, di un tempo che si proietta nell’immagine per stabilire un’unità tra l’essere e il divenire».7

Nel 1967, dunque, l’inserimento del soggetto nell’opera, il coinvolgimento dello spettatore, la perdita della fissità dell’immagine e l’intuizione della temporalità sono tutti elementi che conducono la ricerca dell’artista verso una spazialità sempre più inclusiva, in cui la corporeità dell’osservatore interrompe la dimensione contemplativa della frontalità. Non solo, in East Village e Glosty, entrambi del 1967, i materiali industriali e freddi sostituiscono il dinamismo dei pannelli con una fisicità delle silhouette modulate tra rarefazione e densità, fino a dissiparsi nello spazio con Sunset light, sempre dello stesso anno.

Portare dentro il visivo la manifestazione di una soggettività è operazione assai comune intorno alla fine degli anni Sessanta, soprattutto se si considerano gli orientamenti performativi, dove la presenza del corpo si rivela in relazione ai processi di decentramento sia rispetto ai confinamenti proposti dalle categorie artistiche, sia rispetto alle possibilità di autorappresentazione del soggetto stesso, aspetto particolarmente significativo per le posizioni femministe.

Sono questi gli anni in cui Laura Grisi inizia la sua ricerca più radicale, dove fenomeni ed elementi naturali sono riprodotti ed esplicitamente mostrati nelle loro forze generatrici riprodotte artificialmente in spazi chiusi, con l’uso di ventilatori puntati alla massima velocità, luci antinebbia e fumo, lampade al neon, tubature e vasche, fonti luminose ad alta intensità e lastre di piombo.

Si tratta di Wind Speed 40 Knots del 1968, Un’Area di Nebbia del 1969 e, infine, Volume d’aria, Drops of Water, Luce + Calore = Tempo di Fusione del 1970, attori di una «femminilizzazione dello spazio»,8 in cui è presente quella «tensione a uscire dal presidio teorico maschile e occidentale di una cristallizzazione delle materie e delle sostanze, così come dalle forme di assoggettamento a cui hanno dato luogo nella storia».9 Sono spazi che il soggetto, e per prima l’artista stessa, deve attraversare «come se» davvero si vivesse quella situazione per la prima volta, dove il «come se» per Grisi non è forma di alienazione momentanea ma esercizio continuo di ri-collocazione nel presente, una strategia per sfuggire alle traiettorie monologiche del pensiero e tracciare nuovi percorsi di mutamento.

Questa deriva nello spazio indicata dai primi ambienti è la premessa a un nuovo nucleo di lavori, elaborati tra il 1969 e il 1972. Sono lavori che, con Rosi Braidotti, possiamo definire «performance nomadiche»,10 pensate già come «mappe retrospettive»,11 in cui alla «femminilizzazione dello spazio» si aggiunge, così, anche quella del tempo.

In queste azioni Laura Grisi si proietta fuori dallo spazio del fotografico, dal quadrato della rappresentazione e da quel «come se», per stabilire una nuova posizione che si dà in rapporto a una grandezza che lei stessa riconosce incommensurabile ma intellegibile allo stesso tempo e dall’esito imprevisto o invisibile. Dislocata anche rispetto alla linearità del tempo, la vediamo davanti all’infinito, rannicchiata tra le dune di una spiaggia per contarne i granelli (The Measuring of Time, 1969), in una cava di ciottoli per cercare tutte le possibili combinazioni dei ciottoli accatastati (From One to Four Pebbles, 1972), attaccata a un albero e sdraiata al suolo con un microfono in mano per registrare il suono della crescita della pianta e il rumore dello spostamento delle formiche sul terreno (Sounds, 1971) o, infine, impegnata a stendere delle istruzioni per esercitarsi e far esercitare sulla capacità dell’approssimazione e della permutazione come scienza più esatta dell’equivalenza matematica (Distillations: Three Months of Looking, 1970). Un agire «nomadico», questo, non perché corrispondente a una dimensione del viaggio, pur vissuta profondamente da Grisi, ma in quanto stato mentale e intellettuale, una forma di «coscienza critica che si sottrae, non aderisce a formule del pensiero e del comportamento socialmente codificate».12

Ecco che, giunti a questo punto, si chiarisce definitivamente anche l’analogia del pensiero di Laura Grisi con l’immagine del beduino nel deserto dove, sebbene congelati in una fotografia di reportage, troviamo tutti gli stadi di quel procedere nomade che ridefinisce la sua «identità» sia di artista, sia di soggetto conoscente e conoscibile in continuo movimento. Se l’artista si allontana da una traccia è per lasciarne un’altra più avanti e un’altra ancora, moltiplicandole all’infinito e quindi smaterializzandole, poco importa se resteranno invisibili, perché il nomade, a differenza del cartografo, «sa come leggere mappe invisibili, o mappe scritte nel vento, sulla sabbia e i sassi».13

Arte e Critica, n. 96, autunno – inverno 2021, pp. 38-43.

1. La fotografia è stata pubblicata in G.Celant, Laura Grisi. A Selection of Works With Notes by the Artist, Rizzoli, New York 1990, con la dicitura A nomad and “his mosque” (a stone square in the desert), Saudi Arabia. L’anno non è riportato.

2. Si fa qui riferimento al titolo del celebre testo di R.Braidotti, Soggetto nomade. Femminismo e crisi della modernità, Donzelli Editore, Roma 1995 (1994).

3. Laura Grisi. The Measuring of Time, a cura di Marco Scotini, Muzeum Susch, Susch, 5 giugno – dicembre 2021.

4. M. Scotini, Laura Grisi. The Measuring of Time, exhibition booklet, p.44.

5. Ivi, p.45.

6. V. I. Stoichita, Breve storia dell’ombra. Dalle origini della pittura alla Pop Art, Il saggiatore, Milano 2003, p.98.

7. Ibidem.

8. M. Scotini, op.cit., p.51.

9. Ibidem.

10. R. Braidotti, op.cit., p.9.

11. Ibidem.

12. Ivi, p.8.

13. Ivi, p.21.

Among the 5,000 photographs taken by Laura Grisi from the late 1950s to the late 1960s, during the long journeys she made together with her documentary film director husband Folco Quilici, is probably concealed the sign of her impatience towards the alleged fidelity to reality attributed to the photographic medium.

Among the shots, there is one in particular that, as in a rebus, anticipates the themes of her artistic research starting from the assumption that in photography, especially documentary photography, one is never included as subject except in the exercise of a power that is the privilege of an ethnocentric gaze.

The photograph is entitled A nomad and “his mosque” (a stone square in the desert)1 and it shows a man in the desert of Saudi Arabia, with his back turned in the act of walking towards the horizon, at his foot a rectangular shape circumscribed by irregular stones, which are larger at the four vertices. The proximity and the attitude of the man next to that perimeter suggest a primitive act of delimitation of a space, followed by its abandonment.

This scene, contextualized in the artistic path taken by Laura Grisi, lends itself to a deeper reading. That rectangle seems to simulate the geometry of the frame and therefore a space assigned to representation, undisputed topos of the modernist tradition, further defined because it is inserted in turn inside the frame of the photograph and as a «mosque» – as indicated by the title – also connoted as «sacred». The nomad detaches himself from it after having set it up, as does the artist who, after having photographed it, will separate herself both from the image, in order to move on to the next one and, later on, from that type of shooting because she is disillusioned by the result.

One last element remains, the desert, where that «nomadic subject»2 moves, deciphers and buries the traces of his passage, thus making the idea of infinity and change resound, still something close to the invisible space of the «sacred» indicated by the «mosque».

A nomad and “his mosque” is, therefore, an image that already outlines, for the meaning of these contents, the relationship that the artist will establish with the dimension of immateriality, necessary because of the awareness acquired with respect to the incompleteness of the methods of representation in the translatability of reality.

This is also one of the themes developed by the recent retrospective dedicated to her at the Muzeum Susch, curated by Marco Scotini.3 The exhibition investigates, in fact, how the objective rendering of reality attributed to photography, in Grisi’s research, while always remaining concealed is literally dismantled and re-presented in the works produced between the Sixties and the Seventies in the only possible way: a conceptual and performative reformulation in which «it will no longer be the single image that is important but the way in which it relates to every other as a case of the possible».4

Between 1965 and 1966 the path undertaken by Laura Grisi begins to distance itself from pictorial representation to verify the dissolution of a univocal idea of center, space, time and identity.

The works presented at the Galleria dell’Ariete in Milan in 1965 mark, in fact, the passage to a painting where in this case the main object is a detailed examination of the functioning of the photographic medium. The pictorial surface becomes a sort of «anatomical table»5 in which fragments of landscape are combined with calculations and diagrams on optics, lenses and degrees of aperture of the diaphragms that in the following Pitture Variabili [Variable Paintings] give way to an element of dynamism: a system of sliding panels that slip on the surface of the painting, allowing the images to overlap and change framing, for an involvement of the observer.

In both series the pictorial space is almost always occupied by the monochromatic silhouette of the artist within the layout of the composition but, in Variable paintings, it is subtracted from the different combinations of the sliding parts. Viewer or author, this shadow-subject is a «fragment» but also an «ambassador of reality within the painting»6 and itself recalls the «image of an ambivalent temporality, of a time that is projected into the image to establish a unity between being and becoming».7

In 1967, therefore, the insertion of the subject into the work, the involvement of the viewer, the loss of fixity of the image and the intuition of temporality are all elements that lead the artist’s research towards an increasingly inclusive spatiality, in which the corporeity of the observer interrupts the contemplative dimension of frontality. Besides, in East Village and Glosty, both from 1967, the industrial and cold materials replace the dynamism of the panels with a physicality of the silhouettes modulated between rarefaction and density, until they dissipate in space with Sunset light, again from the same year.

Bringing the manifestation of a subjectivity within the visual is a very common operation around the late sixties, especially if we consider the performative tendencies, where the presence of the body is revealed in relation to the processes of decentralization both with respect to the confines proposed by the artistic categories, and with respect to the possibilities of self-representation of the subject itself, a particularly significant aspect for feminist positions.

These are the years in which Laura Grisi begins her most radical research, where phenomena and natural elements are reproduced and explicitly shown in their generating forces artificially reproduced in closed spaces, with the use of fans set at maximum speed, fog lights and smoke, neon lamps, pipes and tanks, high intensity light sources and lead plates.

These are Wind Speed 40 Knots from 1968, Un’Area di Nebbia [A Space of Fog] from 1969 and, finally, Volume d’aria [Volume of Air], Drops of Water, Luce + Calore = Tempo di Fusione [Light + Colour = Melting Time] from 1970, actors of a «feminization of space»,8 in which there is that «tendency towards leaving the male and western theoretical stronghold of a crystallization of materials and substances, as well as the forms of subjection to which they have given rise in history».9 These are spaces that the subject, and first of all the artist herself, must cross «as if» one were really living that situation for the first time, where the «as if» for Grisi is not a form of momentary alienation but a continuous exercise of re-location in the present, a strategy to escape the monologic trajectories of thought and trace new paths of change.

This drift in space indicated by the first environments is the premise for a new body of works, made between 1969 and 1972. These are works that, with Rosi Braidotti, we can define as «nomadic performances»,10 already conceived as «retrospective maps»,11 in which to the «feminization of space» is added, so, also that of time.

In these actions Laura Grisi projects herself out of the space of the photographic, out of the square of representation and out of that «as if», in order to establish a new position that is given in relation to a greatness that she herself recognizes as incommensurable but at the same time intelligible and with an unforeseen or invisible outcome. Dislocated also with respect to the linearity of time, we see her in front of infinity, crouched among the dunes of a beach to count the grains (The Measuring of Time, 1969), in a pebble quarry in search of all the possible combinations of amassed pebbles (From One to Four Pebbles, 1972), attached to a tree and lying on the ground with a microphone in her hand to record the sound of plant growth and the sound of ants moving across the ground (Sounds, 1971), or, finally, engaged in writing the instructions to practice and let people practice the skill of approximation and permutation as a more exact science than mathematical equivalence (Distillations: Three Months of Looking, 1970). A «nomadic» action, this, not because it corresponds to a dimension of travel, although deeply experienced by Grisi, but as a mental and intellectual state, a form of «critical consciousness that avoids, does not adhere to socially codified formulas of thought and behavior».12

And here, at this point, the analogy of Laura Grisi’s thought with the image of the Bedouin in the desert where, even if frozen in a reportage photograph, we find all the stages of that nomadic proceeding that redefines her «identity» both as an artist and as a knowing and knowable subject in continuous movement, is definitely clarified. If the artist moves away from a trace, it is to leave another one further on and another, multiplying them infinitely and thus dematerializing them, no matter if they remain invisible, because the nomad, unlike the cartographer, «knows how to read invisible maps, or maps written in the wind, on sand and pebbles».13

Arte e Critica, no. 96, autumn – winter 2021, pp. 38-43.

1. The photograph was published in G.Celant, Laura Grisi. A Selection of Works With Notes by the Artist, Rizzoli, New York 1990, with the caption A nomad and “his mosque” (a stone square in the desert), Saudi Arabia. The year is not reported.

2. We refer here to the title of R.Braidotti’s famous book, Soggetto nomade. Femminismo e crisi della modernità, Donzelli Editore, Rome 1995 (1994).

3. Laura Grisi. The Measuring of Time, curated by Marco Scotini, Muzeum Susch, Susch, 5 June – December 2021.

4. M. Scotini, Laura Grisi. The Measuring of Time, exhibition booklet, p.44.

5. Ivi, p.45

6. V. I. Stoichita, Breve storia dell’ombra. Dalle origini della pittura alla Pop Art, Il saggiatore, Milan 2003, p.98.

7. Ibidem.

8. M. Scotini, op.cit., p.51.

9. Ibidem.

10. R. Braidotti, op.cit., p.9.

11. Ibidem.

12. Ivi, p.8.

13. Ivi, p.21.