Se il Tempo è portatore di verità, Roman Opalka (1931-2011) ha attraversato questa dimensione per tutta la vita, nel tentativo di avvicinarsi all’abisso dell’infinito attraverso una pratica così radicale che ha visto l’arte identificarsi con l’esistenza stessa.

L’artista polacco ha avviato nel 1965 il suo progetto 1965/1 – ∞ realizzando tele su cui ha trascritto progressivamente, in forma letterale, i numeri da uno a infinito, in bianco su nero, fino a schiarirsi e divenire quasi monocromi. In questo percorso durato oltre quarant’anni, c’è un racconto del Tempo che non è narrativo, né didascalico, ma universale e, allo stesso tempo, relativo, poiché ogni tela ha rappresentato solo “l’impronta” di un momento dell’esistenza, “uno psicogramma”, come lo definiva l’artista. Il numero è scrittura silenziosa, archetipo, ripetizione della forma intervallata da una pausa, uno spazio vuoto, “un interstizio mentale” che potrebbe essere ricollegato alla pratica cinematografica del montaggio, in cui il rimando al successivo diviene formulazione continua di possibilità, dove ripetizione e arresto sono le uniche azioni possibili. Nella costruzione della “durata” rientra il valore universale del tempo che abbraccia e coinvolge l’uomo in quanto specie, per il suo essere nel tempo senza potersene distaccare: «La vita è nel tempo e si sviluppa nell’intervallo tra la nascita e la morte. Per l’uomo, nascita e morte significano inizio e fine del tempo che è concesso».1 Si riconsidera il tempo di osservazione dell’opera che – come ricorda Lóránd Hegyi nel suo recente Roman Opalka’s essentiality 1965/1 – ∞. The artist in his Spiritual Word, edito da Aragno – ricalca il tempo di lettura e riattiva mentalmente l’atto di produzione, il gesto artistico della scrittura. Ma c’è anche una potenzialità sonora nell’opera, nello scandire mentalmente le lettere che formano la cifra c’è una voce, che è quella di chi osserva e legge ma è anche quella dell’artista, che era solito registrarsi al magnetofono mentre scandiva, piano, i numeri in polacco.

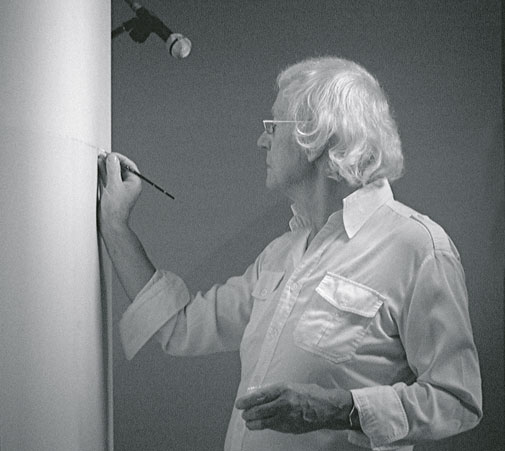

Negli stessi anni in cui anche Boltanski e On Kawara hanno tentato di ricordare il vissuto attraverso forme di catalogazione, Roman Opalka ha scelto di rapportarsi al Tempo né con atto di sfida, consapevole della finitudine dell’uomo, né con accondiscendenza, perché determinato nell’avvicinarsi a una dimensione metafisica di infinito e – stando alla lettura di Hegyi – anche spirituale. Nel comporre il diagramma dell’esistenza, Opalka ha sfidato l’irreversibilità nel seguire il flusso temporale attraverso una traccia pittorica, documentando la sua battaglia con il medium fotografico. Ogni sera, difatti, a partire dal 1972, ha avviato una pratica rituale per cui, mosso «dall’imperiosa necessità di non perdere nulla nel carpire il tempo», si scattava un autoritratto nella medesima posa. Un medium che, nel suo modus operandi, ha attivato un “terzo tempo” con cui confrontarsi, non quello dell’immagine (del numero), non quello dell’evento (dell’azione), ma quello dell’immediatezza: l’istantanea in cui si salva tutto ciò che appare senza possibilità di scomposizione. L’immagine immobile contro lo scorrimento delle sue “costellazioni temporali”. E mentre i chiaro-scuri di luce e ombra sul volto dell’artista si facevano più densi col passare degli anni, la pittura lentamente perdeva la nitidezza del tratto, fondendosi con il colore dello sfondo.

Immediato il riferimento, allora, al Quadrato bianco su fondo bianco di Malevič (1918), in cui si ricercava l’assoluto, dove solo una linea quasi impercettibile scandiva i confini della forma e si tornava al punto zero della pittura.

Le parole di Hegyi sono forse l’ultimo ritratto di Opalka come artista, come uomo e come intellettuale che, mai sottraendosi alla radicalità dell’azione, ha riconnesso l’essere a quell’universalità che non conosce differenze; il suo lavoro, continua Hegyi, può essere considerato una metafora della complessità della pratica artistica universale.

È interessante a questo punto seguire le sue stesse parole:

«L’extraterritorialità radicale dell’opera di Roman Opalka rivela il suo impegno sostanziale nella comunicazione di esperienze fondamentali che gli impedisce di indugiare sul terreno di una comoda, piacevole ed edonistica frammentazione di invenzioni formalistiche e pseudo narrazioni aneddotiche di edonismo estetico, inducendolo al contrario ad abbracciare l’efficace metafora del vivente in senso nietzschiano. La sua pratica artistica sembra essere lontana da qualsiasi forma rassicurante e prestabilita; la sua distanza sublime da ogni potenziale chiarificazione suggerisce l’onnipotenza di un’esperienza originale che è al contempo spirituale e intellegibile, ma anche sensuale fisica ed emozionale, e che rimanda direttamente e sostanzialmente alla totalità indivisibile del vivente.

La straordinaria, quasi sacra solidità del suo lavoro, il rigore radicale, l’intransigenza e l’ascetismo di quest’ultimo, creano un’aura enigmatica attorno allo studio, che è sempre uno spazio metaforico di metamorfosi. In questo spazio, la vita di Roman Opalka si trasforma – quasi ritualmente – in un’opera d’arte. L’atto di metamorfosi ha luogo nello studio; i vari strumenti del processo creativo e della sua documentazione, che è parte integrante dell’intera opera, sono riprodotti come oggetti rituali. La libertà spirituale ed emozionale della sua arte si formula e si genera in questo spazio metaforico di trasformazione spirituale. Quando affermo che l’arte di Roman Opalka è senza tempo e senza dimora, intendo dire che egli non agisce in nome di alcuna minoranza, sia essa nazionale, etnica, religiosa o sociologica, ma che al contrario punta lucidamente a una posizione di totale indipendenza. Questa autonomia intellettuale ed estetica è naturalmente e necessariamente relativa, in quanto indipendenza assoluta non è solo storicamente e ontologicamente impossibile, ma sarebbe anche eticamente inaccettabile. La sua indipendenza intellettuale ed estetica – che è al contempo indipendenza etica e politica – si traduce in un rifiuto della rappresentazione di particolari e isolati gruppi di interesse, con obiettivi ristretti, limitati e pragmaticamente raggiungibili, non importa quanto marcatamente sovrastimati, quali nazioni, religioni, movimenti politici, gruppi sociali, classi, o micro-culture moralisticamente legittime, subculture, minoranze e gruppi marginali. L’opera di Roman Opalka è paradigmatica di una posizione artistica che non può essere interpretata nell’ambito ristretto del dialogo oriente-occidente o del processo culturale intraeuropeo, ma soltanto nel contesto esteso di arte eterna».

Arte e Critica, n. 85, primavera – estate 2016, pp. 76-78.

1. L. Hegyi, Roman Opalka’s essentiality 1965/1 – ∞, Nino Aragno Editore, Milano, 2015, pp.289.

If Time is a bearer of truth, Roman Opalka (1931-2011) went through this dimension throughout his life, in the attempt to get near to the abyss of infinity through such a radical practice that has seen art identifying itself with existence itself.

The Polish artist started his project 1965/1 – ∞ in 1965, creating canvases on which he progressively wrote down, in literal form, numbers from one to infinity, in white on black, until becoming lighter, almost monochrome. In this research that lasted over forty years, there is a narration of Time that is neither narrative nor didactic but universal and, at the same time, relative, because each canvas has represented only the “print” of a moment of existence, a “psychogram”, as the artist defined it. The number is silent writing, archetype, repetition of form spaced out by a pause, an empty space, “a mental interstice” that could be related to the cinematographic practice of montage, in which the reference to the following one becomes a continuous formulation of possibilities, where repetition and interruption are the only possible actions. The construction of the “duration” includes the universal value of time that embraces and involves man as species, for his being in time without being able to become detached from it: “Life exists in time and unfolds in the interval between birth and death. For man, birth and death mean the beginning and the end of the time we are given”.1 One reconsiders the time of observation of the work that – as Lóránd Hegyi reminds us in his recent Roman Opalka’s essentiality 1965/1 – ∞. The artist in his Spiritual Word, published by Aragno – follows the time of reading and mentally reactivates the act of production, the artistic gesture of writing. But there is also a sound potential in the work, in the mental articulation of the letters that make up the cipher there is a voice, which is that of those who observe and read but which is also that of the artist, who used to record himself with the tape recorder while articulating, slowly, the numbers in Polish.

In the same years in which also Boltanski and On Kawara tried to recall lived experience through forms of cataloguing, Roman Opalka chose to relate himself to Time, neither with an act of defiance, aware of the finiteness of man, nor with compliance, because he was determined in coming close to a metaphysical dimension of infinity and – according to Hegyi’s reading – also spiritual. In composing the diagram of existence, Opalka challenged irreversibility in following the time flow through a pictorial track, documenting his battle through the medium of photography. Every evening, in fact, starting from 1972, he began a ritual practice for which, moved by “the imperious need to lose nothing in seizing time”, he took a self-portrait in the same pose. A medium that, in his modus operandi, has activated a “third time” with which to establish a relationship, a time which is neither that of the image (of the number) nor that of the event (of the action), but that of immediacy: the snapshot in which all that appears is recorded, without possibility of decomposition. The immobile image against the flow of its “temporal constellations”. And while the chiaro-scuri of light and shadow on the face of the artist became denser with the passing of time, painting slowly lost the clarity of the line, merging with the colour in the background. Immediate is then the reference to Malevič’s White Square on a White Background (1918), in which there was a search for the absolute, where only an almost imperceptible line marked the boundaries of form and one returned to the zero point of painting.

Hegyi’s words are probably the last portrait of Opalka as an artist, as a man and as an intellectual who, never eluding the radicality of the action, has reconnected the being to that universality that knows no differences; his work, Hegyi continues, can be considered a metaphor for the complexity of the universal artistic practice.

It is interesting at this stage to follow his own words:

“The radical extraterritoriality of Roman Opalka’s œuvre shows his fundamental commitment to the communication of essential experiences, which prohibits him from lingering on the terrain of comfortable, pleasurable, hedonistic fragmentation of formalistic inventions and anecdotal pseudo-narratives of aesthetic hedonism, and instead forces him to embrace the powerful metaphor of living in the Nietzschean sense. His artistic practice seems to be far removed from all comfortable, conventional gestalts; his sublime distance from all potential explanations suggests the omnipotence of a primal experience that is at the time spiritual and intelligible, as well as sensual, physical and emotional, and that relates directly and fundamentally to the indivisible totality of living.

The breathtaking, almost sacred stability of his work, its radical rigorousness, stringency and ascetism form an enigmatic aura around the studio, which is always a metaphorical space of metamorphosis. In this space, Roman Opalka’s life is transformed – quasi-ritually – into a work of art. The act of metamorphosis takes place in the studio; the various implements of the creative process and its documentation, which is an integral part of the total work of art, are remade as ritual objects. The spiritual and emotional homelessness of his art formulates and generates itself in this metaphorical space of spiritual transformation.

When I say that Roman Opalka’s art is timeless and homeless, I mean that he does not become active on behalf of any minority, be it national, ethnic, religious or sociological, but instead deliberately strives for a completely independent position. This intellectual, aesthetic independence is naturally and necessarily relative, as absolute independence is not only historically and ontologically impossible, but would also be ethically inacceptable. His intellectual and aesthetic independence – which is also ethical and political independence – means a rejection of the representation of isolated special interest groups with narrow, limited and pragmatically achievable objectives, no matter how dramatically overrated they may be, such as nations, religions, political movements, social groups, classes, or moralistically legitimated micro-cultures, subcultures, minorities and marginal groups. Roman Opalka’s œuvre is paradigmatic of an artistic position that cannot be interpreted within the narrow, restricted framework of the East-West dialogue or the intra-European cultural process, but only in the limitless context of eternal art”.

Arte e Critica, no. 85, spring – summer 2016, pp. 76-78.

1. L. Hegyi, Roman Opalka’s essentiality 1965/1 – ∞, Nino Aragno Editore, Milan, 2015, pp.289.