Il paesaggio visuale del Cairo ancora oggi permette di leggere le dinamiche e le istanze della protesta che nel febbraio 2011 hanno portato alla caduta del regime di Hosni Mubarak e il ruolo che l’arte, attraverso la trasformazione dello spazio pubblico, ha avuto sia nella fase della rivolta che in quella di democratizzazione. «Penso che il risultato creativo di questa rivoluzione ancora in corso sia parte integrante della sua continuazione e della direzione che è destinata a prendere»1, ha dichiarato l’artista Mohamed Fahmy noto come Ganzeer, esprimendo la consapevolezza di un’arte non solo determinante ma intrinseca al processo rivoluzionario. Da subito le pratiche artistiche (con il canto e le danze, il rap, la pittura, la poesia, le vignette)2 hanno costituito il cuore della resistenza di piazza Tahrir e hanno contribuito a creare e a diffondere un immaginario che ha alimentato lo spirito della rivoluzione, in una lotta che ha contrapposto alla forza della repressione la creatività della nonviolenza. Così quando l’architetto e grafico Shady Youssef celebrava nella piazza il crollo del regime disegnando l’immagine del re caduto degli scacchi, poi replicata per le strade dal graffitista El Teneen, affermava la vittoria dell’insurrezione giovanile attraverso la metafora sovversiva del gioco e della dimensione estetica utilizzata dai dadaisti. La stessa che ritroviamo nei segnali stradali capovolti e decostruttivi di Nazeer che portano alla strada della “liberazione” – traduzione italiana di Tahrir – o ancora nelle garitte “occupate” e snaturate dai graffiti antimilitaristi, tracce delle esperienze di anarchia estetica e libertaria elaborate dalla piazza.

Dove, racconta ancora Youssef, i giovani urbanisti dimostranti, anziché proporre interventi di pianificazione e di coordinamento spaziale, preferivano osservare la spontanea organizzazione di ciò che Beuys chiamerebbe una scultura sociale, che si andava costituendo come un laboratorio di consapevolezze condivise di partecipazione, nonviolenza, diritti umani e delle donne, convivenza interreligiosa, determinanti per la costruzione di nuove identità democratiche. Una sperimentazione ancora visivamente leggibile in uno straordinario paesaggio urbano rivoluzionario che spiazza le aspettative e gli stereotipi dello sguardo occidentale e riafferma il legame tra arte e nonviolenza: dagli stencil nei quali si fronteggiano il fucile (“loro”) e la videocamera (“noi”), o il dito di chi argomenta e la pistola sulla scritta “pacificamente” che scandisce l’ingresso di una delle moschee dell’Università del Cairo, al carro armato a dimensioni reali di Ganzeer, puntato contro il giovane ciclista che trasporta il pane, chiamato in arabo “vita” e simbolo di identità nazionale. Un’iconografia della sproporzione tra viltà degli uomini armati e coraggio degli inermi, che, da Goya a Picasso passando per Manet, attraversa la «storia dell’arte come storia dell’agire nonviolento», secondo una bella definizione di Argan.3 E ancora al ciclo del graffitista Anwar sul Battaglione di Monna Lisa (che colpisce i volti grotteschi e cangianti del regime che fioriscono come piante infestanti) e può essere considerato un’allegoria della pittura come arma nonviolenta.

In questa battaglia per la libertà, dallo spazio aperto del web a quello reale delle strade e delle piazze, le nuove tecnologie hanno permesso la diffusione massiva non solo delle prassi dell’azione nonviolenta (come il manuale Dalla dittatura alla democrazia di Gene Sharp)4 ma anche dei contenuti e delle tecniche del graffitismo (come lo stencil booklet dello stesso Ganzeer5 con «disegni… ready made che ognuno può stampare, incollare su cartoncino, tagliare ed usare» che sembra una versione 2.0 dei procedimenti warholiani di riproducibilità e creazione seriale e collettiva). E attivisti e artisti, sin dai primi giorni delle proteste di massa avevano fatto circolare una guida visiva alle modalità, alle strategie e agli «obiettivi della disobbedienza civile».6 Dove è sintomatico che l’abbigliamento dei dimostranti, oltre alla bomboletta spray da spruzzare sui parabrezza, sulle videocamere di sorveglianza dei mezzi militari e sugli elmetti dei poliziotti (per impedire loro di “vedere”), includeva le rose, un riferimento alla precedente rivoluzione nonviolenta tunisina ma anche al celebre graffito di Banksy con il giovane antagonista che lancia un mazzo di fiori.

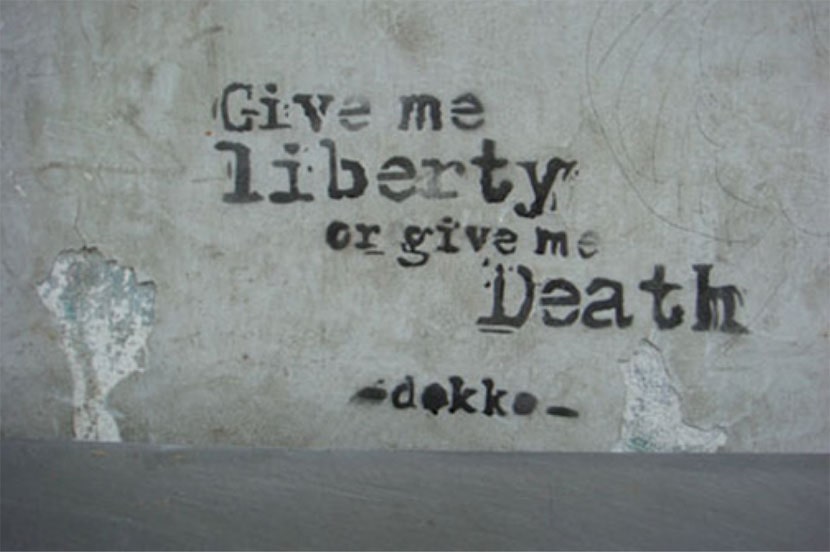

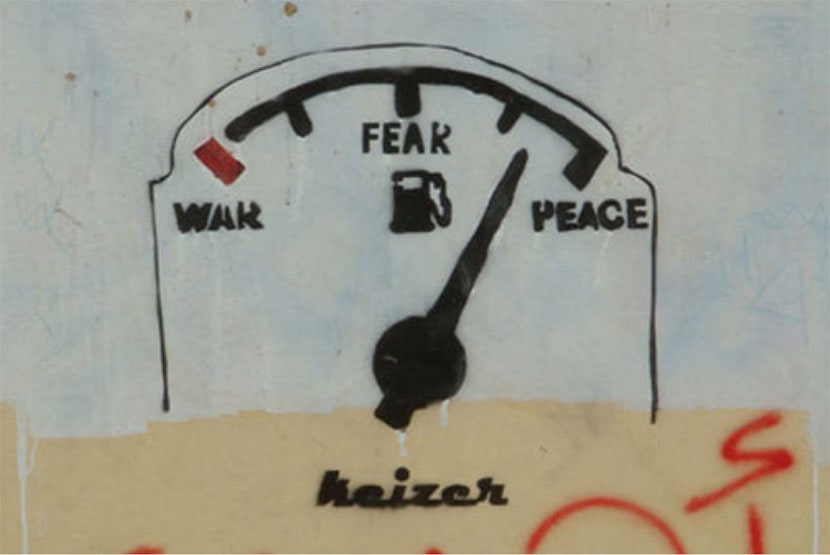

L’analisi dei contenuti dei graffiti del Cairo mostra la loro specificità – in termini sociali, politici e culturali – all’interno del più generale antagonismo della Street Art come movimento globale. Così in uno spirito identitario nazionalista gli eventi contemporanei si intrecciano con la memoria delle lotte indipendentiste e rivoluzionarie del paese e con l’immaginario della cultura di massa, in una ibridazione di generi e citazioni che va dagli slogan degli ultras a quelli della resistenza palestinese (Respect Existence or Expect Resistance a firma Keizer), alla maschera di Guy Fawkes del film V for Vendetta divenuta il simbolo globale delle proteste del 2011,7 al pensiero di Camus, al fumetto e all’adbusting (dal Nescafé al NoSCAF, No Supreme Council of Armed Forces), all’interpretazione delle iconografie faraoniche e dei geroglifici, con messaggi diretti e facili da ricordare nella sintesi di visuale e verbale tipica del graffitismo. Come racconta la blogger Soraya Morayef (Suzee) «la Street Art continua ad ispirare e a motivare gli egiziani… non solo per le idee e i messaggi degli artisti ma per la resilienza e la determinazione che essi mostrano continuando a illuminare, a protestare e ad educare il passante con la propria arte».8 E le modalità dei giovani graffitisti sono talmente entrate nella vita politica egiziana da essere state utilizzate nell’ultima campagna elettorale non solo con finalità di contestazione ma come integrazione dei tradizionali metodi di comunicazione dei candidati.

Lo sviluppo delle prassi artistiche nel contesto della rivoluzione, con l’occupazione fisica e non solo visiva della città, ha dunque determinato una riappropriazione della visualità e dell’immaginario collettivo e, con la democratizzazione dello spazio pubblico tramite meccanismi creativi antagonisti a quelli e del sistema artistico e del “consumo culturale” di matrice capitalistica, anche un’idea di democratizzazione dell’arte, secondo quanto dichiarato da Ganzeer: «Le strade sono di tutti. Le gallerie sono per una nicchia che va alla ricerca dell’arte. È sbagliatissimo che le strade siano così aperte agli effetti del lavaggio del cervello di pubblicitari a guida capitalistica e così chiuse ad un’arte onesta che è stata intrappolata nei confini di gallerie dal falso costrutto. Le gallerie devono esistere ma non dovrebbero essere l’unico modo per fare esperienza dell’arte».10 E ancora: «Adesso la gente partecipa e ha cura del proprio destino. Non so se durerà, ma dopo la rivoluzione c’è stata una svolta culturale nel modo in cui la gente si rapporta con le strade».

La battaglia estetica per le vie del Cairo – quasi una continuazione di quella di piazza Tahrir – sembra essersi sviluppata con una semantica del mostrare e coprire, dello svelare e nascondere: labbra cancellate (dove il diritto di parola negato è restituito dal linguaggio dello sguardo) o imbavagliate (come nella pubblicità della Freedom Mask prodotta dalla giunta militare allora al potere in un ironico manifesto di Ganzeer che ne determinò l’arresto nel maggio 2011); sguardi imprigionati dietro le sbarre, o di vigilanza democratica delle videocamere degli attivisti; o, in una assimilazione configurativa di occhio, tv e oblò della lavatrice, sguardi anestetizzanti e propagandistici dei media controllati dal potere. E ancora, occhi degli ottocento giovani di piazza Tahrir accecati dalla polizia durante le dimostrazioni (ai quali si riferiscono gli stencil con il Wanted di uno dei responsabili, processato e poi rilasciato, che ricordano Warhol non solo per la sua serie sul tema dei ricercati ma soprattutto per lo sdoppiamento reiterativo dell’immagine), gap come dettagli inquietanti che affiorano da un livello altro di spazialità, quello del rimosso della memoria, e volti del potere a loro volta accecati nei manifesti in una sorta di contrappasso simbolico che denuncia anche un altro tipo di cecità. Questa partita del mostrare e nascondere si gioca anche su e attorno al corpo della donna: un tema presente nella drammatica vicenda, resa nota da YouTube ed evocata dai molti stencil del reggiseno blu, di Alia El Mahdy, la ragazza di piazza Tahrir (nota come “la rivoluzionaria nuda” o “blue bra girl”) brutalmente picchiata, trascinata dalle forze dell’ordine e scoperta dell’hijab (il velo culturalmente simbolo di modestia e di moralità), per essere umiliata pubblicamente nella sua dignità e decenza, e poi ricoperta da un altro poliziotto in un gesto di pudore. Un livello di violenza anche sessista, ricordato pure dagli stencil che raffigurano Samira Ibrahim circondata da un esercito che ha il volto del medico (da lei denunciato e rimasto impunito) che le effettuò il test di verginità, praticato sulle dimostranti come forma intimidatoria e di ritorsione sociale.9

Ma è il tema dei martiri, come vengono chiamate nella cultura profondamente religiosa del paese le vittime della repressione, a dominare: il volto del 27enne Khaled Said, la cui brutale uccisione ha determinato le proteste culminate nel 25 gennaio 2011, appare per le strade del Cairo con un’evanescenza fantasmatica e surreale. Assieme alle immagini dell’artista Ahmed Basiony, morto mentre filmava le dimostrazioni (un lavoro postumo che ha rappresentato l’Egitto all’ultima Biennale di Venezia) o di Alaa Abd El-Fattah e dello sheikh Effat uccisi a piazza Tahrir e che, associati a quella dell’attivista Mina Daniels, vittima del massacro dei cristiani dell’ottobre 2011, sono divenuti i simboli della rivoluzione e dell’unità religiosa in Egitto. «I volti dei martiri e degli attivisti incarcerati continuano a proliferare sui muri – racconta Morayef – …come memoria visiva e stimolo emotivo della nostra recente, spesso traumatica storia… Per me si tratta di arte e storia nel suo farsi ed è stata la prima volta che ho visto un graffito come forma d’arte per riflettere la realtà e registrare la storia in tempo reale».11

La verità delle immagini che ricordano l’impunità dei responsabili delle repressioni e dei massacri, gli arresti ingiustificati e le violazioni dei diritti (dallo scoppio della rivoluzione ci sono stati oltre 12.000 giovani arrestati e condannati da tribunali speciali), in un uso dello spazio pubblico che diviene esercizio di memoria, demistificazione e svelamento, ha determinato la censura dei murales da parte delle autorità militari. Spingendo gli artisti a rispondere nel 2011 con l’organizzazione di un Mad Graffiti Weekend (pubblicizzato dall’immagine dello spray contro il fucile), una realizzazione collettiva di stencil aperta a calligrafi, fotografi, videomaker, blogger, giornalisti, scrittori, pubblicitari, writer,12 seguita nell’anniversario della rivoluzione da una settimana di mobilitazione a Mohamed Mahmoud street che fu sede cruenta di scontri. Strategicamente significativa per la sua vicinanza a piazza Tahrir, la via ancor oggi è al centro di un conflitto tra la volontà degli artisti di “far vedere” per non dimenticare e l’iconoclastia del potere che intende sottrarre allo sguardo il ricordo degli eventi, in un’opposizione sempre antica e sempre nuova che riporta al ruolo della memoria nelle lotte per la verità e la giustizia dell’America Latina e alle dinamiche della storia e dell’arte, tra oblio e memoria e tra memoria e immaginazione.13 Con murales a più mani e in divenire, coperti, ridipinti e da poco nuovamente cancellati, la strada si è trasformata nel luogo della satira politica, con le raffigurazioni sarcastiche del serpente con le teste dei generali, del burattinaio e dei burattini (i militari e i politici), cancellati poco prima delle elezioni ma ridipinti con i volti dei candidati alle presidenziali; della testa metà Mubarak metà Tantawi (comandante della giunta), coperta ma rimpiazzata dall’immagine di un artista che combatte con pennello… Ma con le sue stratificazioni e cancellazioni è soprattutto divenuta uno specchio della memoria e un sito di compassione e preghiera, di identità e coscienza collettiva per le scene epiche di battaglia con figure di miti egizi, opera di Alaa Awad e Hanaa El Degam, come una moderna Guernica della fase rivoluzionaria, e per gli sguardi delle giovani vittime del massacro di Port Said del 2012 di Ammar Amo Bakr, integrati dai volti delle madri che mostrano le foto dei figli scomparsi, con le stesse dinamiche ostensorie delle Madri argentine di Plaza de Mayo. Dove il “vedere e toccare” interno alla semiosi dell’immagine ne attesta il valore di verità e di presenza. Un trompe-l’œil che ha anche consentito di vedere spazi di libertà (affrescati dagli artisti) oltre i muri e le barricate alzate dopo la rivoluzione dalla giunta militare per mantenere il controllo degli accessi a piazza Tahrir e prevenire nuove proteste di massa. In una “immaginazione al potere” che ha sostenuto la lotta per il rovesciamento di un regime e la formazione di nuove consapevolezze democratiche, affermando, anche in una cultura tradizionalmente astratta ed aniconica come quella islamica, il potere delle immagini.

Arte e Critica, n. 72, Ottobre – Dicembre 2012, pp. 124-125.

1. In M. Kennard, Global Art Uprising: How the revolutionary spirit transformed creativity, in “The Comment Factory”, 27 February 2012, http://www.thecommentfactory.com/the-global-art-uprising-how-the-revolutionary-spirit-transformed-creativity-6220/

2. Sull’argomento cfr. A.Meringolo, I ragazzi di piazza Tahrir, Clueb, Bologna 2011, pp.83-93, e E.Ferrero, Cristiani e musulmani, una sola mano, Emi, Bologna 2012, p.14.

3. G. C. Argan, “La storia dell’arte”, in Storia dell’arte come storia della città, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1993, p.80.

4. G. Sharp, Come abbattere un regime. Dalla dittatura alla democrazia, Chiare Lettere, Milano 2011.

5. In http://ganzeer.blogspot.com.es/2011/07/free-downloadable-revolutionary-stencil.html#!/2011/07/free-downloadable-revolutionary-stencil.html

6. In A. C. Madrigal,Egyptian Activists’ Action Plan: Translated, in “The Atlantic”, 27 January 2011, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/01/egyptian-activists-action-plan-translated/70388/

7. J. Jones, Occupy’s V for Vendetta protest mask is a symbol of festive citizenship, in “The Guardian”, 4 November 2011.

8. S. Morayef, For the Love of Graffiti: Cairo’s Walls Trace History of ColourfulRevolution, 20 September 2012, in http://suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com/

9. In M. Kennard,Global Art Uprising.., cit.

10. Cfr. Meringolo, cit.,p.63.

11. In For the Love of Graffiti…, cit.

12. Nell’appello agli artisti (in http://streetfiles.org/photos/detail/1240481/) Ganzeer scriveva che «l’unica speranza che abbiamo in questo momento è distruggere la Giunta militare usando l’arma dell’arte».

13. Per cui rinvio a Museums for Peace: A contribution to Remembrance, Reconciliation, Art and Peace, Proceedings of the 5th International Peace Museums Conference, Gernika Foundation, Gernika, Spain, 1-7 May 2005.

THROUGH THE STREETS OF CAIRO

Today Cairo’s visual landscape still helps us understand the dynamics and the demands behind the protest which, in February 2011, caused the fall of the regime of Hosni Mubarak, as well as clarifying the role played by art through a transformation of public space during both the stages of insurrection and democratization. “I think the creative result of this still ongoing revolution is an essential part of its follow-up, as well as of the direction it is destined to take”1: stated artist Mohamed Fahmy, known as Ganzeer, expressing the awareness of an art that is as crucial as much as inherent to the revolutionary process. From the very beginning, artistic practices (along with singing and dancing, rap, painting, poetry and comics)2 have constituted the heart of the resistance in Tahrir Square, and have contributed to creating and spreading a kind of imagery on which the revolutionary spirit has been feeding, in a fight that has counterposed the creativity of nonviolence to the brutality of repression. Therefore, when the architect and graphic designer Shady Youssef was celebrating the fall of the regime by drawing in the square the image of the King’s defeat after a chess match – an image that was eventually recaptured by graffiti artist El Teneen through the city’s streets – he was claiming the victory of young people’s insurrection by adopting, at the same time, the subversive metaphor of the game and of the aesthetic dimension also used by Dada artists.

We can find the same metaphor in Nazeer’s overturned and deconstructed traffic signals which lead to a road of “liberation” – translation of Tahrir – or also in the sentry boxes “occupied” and disfigured by anti-militarist graffiti artists, traces of the aesthetic and libertarian anarchism that had been developed in the square. A square where, according to Youssef, young city planners demonstrators rather than proposing planning interventions or acts of spatial coordination, chose to observe the spontaneous organization of what Beuys would call “a social sculpture”, something that was forming itself into a workshop of shared awareness where people were conscious of their own involvement, nonviolence, human and women’s rights, and interreligious coexistence, all these elements being indispensable for building new democratic identities.3 A kind of experimentation which is still visible within an extraordinary revolutionary urban landscape that does not fit the expectations and the stereotypes of the Western gaze, and reaffirms the connection between art and nonviolence. This ranges from a series of stencils in which guns (“them”) and video cameras (“us”), or the finger of someone arguing and a hand gun aimed on the word, “peacefully”, which marks the entrance to one of the mosques belonging to the University of Cairo, are facing one another, to the graffiti in which a full sized tank by Ganzeer is heading for a young cyclist carrying some bread, which is called “life” in Arabic, and stands as a symbol of national identity.

An iconography of the imbalance between the cowardice of armed men and the courage of the defenseless which, from Goya to Picasso through Manet, has passed through “the history of Art as a history of acting nonviolently”, according to a beautiful definition provided by Argan.4 Another example is the cycle by the graffiti artist Anwar with the Battalion of Mona Lisa (which strikes the grotesque and continually changing faces of the regime as they thrive like infesting plants), a work that can be considered as an allegory of painting as a nonviolent weapon. In this fight for freedom, going from the open space of the web to the real space of streets and squares, not only have new technologies allowed the extended diffusion of a nonviolent praxis (such as described in Gene Sharp’s manual From Dictatorship to Democracy5), but they have also broadened the diffusion of contents and techniques of graffiti (like the “stencil booklet” created by Ganzeer,6 featuring “ready-made designed stencils that anyone can print, glue onto a piece of cardboard, or cut & use”, a work that looks like a 2.0 version of Warhol’s processes of reproducibility, and serial and collective creation). Since the very early days of the mass protests, many artists and activists have been circulating a visual handbook explaining the procedures, the strategies and the “goals of civil disobedience”.7

And it’s symptomatic that the protesters’ clothing included spray cans, that were used to spray windscreens, military vehicles’ security cameras as well as policemen’s helmets (in order to prevent them from “seeing”), and roses, whose presence stand as a reference to the previous nonviolent revolution in Tunisia,8 and also to the celebrated graffiti by Banksy, featuring a young rebel who is throwing a bunch of flowers. An analysis of the contents of Cairo’s graffiti reveals their specificity – from a social, political as well as a cultural perspective – inside a more general antagonism of Street Art as a global movement. Thus, in a spirit of nationalist identity, contemporary events intertwine with the memory of the country’s independence and revolutionary battles, and with the imagery of mass culture, in a sort of hybridization of genres and quotations, ranging from the slogans of football hooligans, to the punch lines adopted by the Palestinian resistance (Respect existence or expect resistance signed by Keizer)9, to the Guy Fawkes’ mask in the film V for Vendetta, an image that has become a global symbol of the 2011 protests,10 to Camus’ thought, to the comics and the “adbusting” (from Nescafé to NoSCAF, No to the Supreme Council of Armed Forces), to the interpretation of Pharaohs iconographies and hieroglyphics, with easy to remember, direct messages thanks to that synthesis of visual and verbal that is so typical of graffiti. The blogger Soraya Morayef (Suzee) says that “street art continues to inspire and motivate Egyptians…, not only for the artists’ ideas and messages, but also for the resilience and determination that they demonstrate in continuing to enlighten, protest and educate passersby with their art”.11

Moreover, the procedures adopted by these young graffiti artists have seeped into Egyptian political life so much that they have also been used during the last election campaign, not only to serve the purpose of the protest, but also as an integration of the candidates’ traditional methods of communication. The development of artistic practices within the context of the revolution, through physical, and not only visual, occupation of the city, has allowed a repossession of both visual and common imagery; and through the democratization of public space – made possible by a series of creative mechanisms opposed to those of the art system and of a capital-borne “cultural consumption” – such development has also given birth to the idea of a democratization of art, as declared by Ganzeer: “Streets belong to everyone. Galleries just represent a niche of people who are in search of art. It is terribly wrong that streets are so open to the brainwashing mechanisms created by capitalistic advertisers, they are closed to an honest art that has been trapped inside falsely conceived galleries. Galleries must exist, but shouldn’t be the only way to experience art”.12 He also said: “Today people contribute to their own destiny and take care of it. I don’t know whether it will always be like this, but after the revolution there has been a cultural change in the way people relate to the streets”. The aesthetic conflict going on through the streets of Cairo – one that is almost a continuation of the battle in Tahrir Square – seems to have developed with a semantics based on revealing and concealing, on showing and hiding: erased lips (where the denied right to talk is restored by a language based on the look) or gagged (as occurs in the commercial of the Freedom mask produced by the then-ruling military council, featured in an ironic placard by Ganzeer, which led to the latter’s arrest in May 2011); imprisoned looks behind bars, or looks of democratic surveillance of the activists’ security cameras; or, the anaesthetizing and propagandist looks of mass media controlled by power, suggested by a configurative assimilation of an eye, a TV and a washing machine porthole. And also, the eyes of the eight-hundred young people blinded by the Police in Tahrir Square during the street demonstrations (the event is addressed by the stencils with the “Wanted” writing referring to one of the offenders, who was tried and eventually released; which not only remind us of Warhol’s series dedicated to wanted people, but above all they make us think of him because of the repetitive splitting of the image); they appear as gaps, as unsettling details arising from a different level of spatiality, one that concerns the repressed contents of memory, while the faces of the powerful in turn appear as equally blinded in the placards, in a type of symbolic retaliation which denounces yet another kind of blindness. Such game of revealing and concealing is also played on and around the female body: a topic that is present in the dramatic event – made famous by YouTube and recalled by the numerous stencils depicting the blue bra – that involved Alia El Mahdy, the girl from Tahrir Square (known as “the naked revolutionary girl” or “the blue bra girl”), who was brutally beaten up, taken away by the police and stripped of her hijab (the veil that culturally symbolizes modesty and morality), then publicly humiliated and deprived of her dignity and decency, and was eventually reclothed by a policeman, in an attempt to recover her modesty. This level of violence becomes, then, also sexist, as configured by the stencils that depict Samira Ibrahim surrounded by an army with the facial features of the same doctor – denounced by the girl and still, never punished – who performed a virginity test on her, the same that was also carried out on other Egyptian female protesters, as a form of intimidation and social retaliation.13 However, the main issue concerns the martyrs, as all victims of repression in the deeply religious culture of this country are called; and the face of 27-year-old Khaled Said (whose brutal murder inflamed the protests culminating in the riots on 25th January 2011)14 appears on the streets of Cairo with a spectral and surreal elusiveness, along with those of the artist Ahmed Basiony, who died while filming the protests (a posthumous work which represented Egypt at the latest Venice Biennale), of Alaa Abdel Fatah and Sheikh Effat, both killed in Tahrir Square. Together with the activist Mina Daniel, a victim of the massacre of Christians in October 2011, they have become the symbols of the revolution, as well as of the inter-religious unity in Egypt. “The faces of the martyrs and of the imprisoned activists are appearing more and more on the walls”, states Morayef, “…similar to a visual memory, an emotional incentive feeding our history, which has often been a traumatic one… In my opinion, all this represents, at the same time, a type of art and a way history makes itself, and for the first time I have considered graffiti as a form of art that is able to mirror reality, while recording real-time history”.15 The truth of the images that remind the impunity of those who were responsible for all the repressions and murders, the unjustified arrests and the acts of violation of human rights (since the outbreak of the revolution, over 12,000 young people have been arrested and condemned by special courts) has turned the use of public space into an exercise of memory, as well as a trained act of demystification and unveiling, and has brought about the censorship of the mural paintings by the military authorities. This spurred the artists to reply in 2011 by organizing a Mad graffiti Weekend (advertised by the image of the spray can against the gun), a collective creation of stencils open to calligraphers, photographers, video makers, bloggers, journalists, writers, advertisers.16

On the anniversary of the revolution, the event was followed by a month-long mobilization organized in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, the same place where ferocious riots had taken place, and where many young people had been beaten and blinded. Being strategically significant because of its proximity to Tahrir Square, this location is, to this day, at the centre of a conflict between the artists’ will to “let people see” the truth in order not to forget what happened, and the iconoclastic drive of a power that aims at remove the memory of past events from everyone’s sight. It is an ancient and yet, always up-to-date opposition, one that claims back the role of memory in the struggles for truth and justice in Latin America, as well as referring to the dynamics of history and art, between oblivion and memory, between memory and imagination.17 Thanks to a series of collective, continuously evolving, covered, repainted and eventually re-erased mural paintings, the street has now become a place for political satire, showing several sarcastic images, such as the one of a snake with the heads of local generals, or another one with a puppeteer with his puppets (referring, respectively, to military chiefs and politicians), which was erased just a couple of days before the elections, but was repainted with the faces of the candidates for the presidential elections. Another mural painting shows a head divided in two halves, one of which has the features of Mubarak, while the other has the face of Tantawi (chairman of the Supreme Council); it was covered, but eventually replaced with the image of an artist fighting with brush and colors… However, with all its stratifications and deletions, the street has become, above all, a mirror of memory as well as a site for compassion and prayers, of identity and collective consciousness because of those epic fighting scenes with images of Egyptians myths, such as in the work by Alaa Awad and Hanaa El-Degham, a modern Guernica dedicated to the revolution, and for the looks of the young victims massacred in Port Said in 2012. Depicted by Ammar Amo Bakr, they have been merged by the artist with the faces of their mothers, who show their murdered children’s pictures with a set of ostensive gestures that remind us of the Argentinean Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. And where the acts of “seeing and touching”, which are internal to the semiosis of the image, testify to its value of truth and presence. This visual scenario becomes therefore a trompe-l’œil, that has also allowed us to see spaces of freedom (painted by the artists) beyond the walls and barricades constructed by the military council after the revolution, in order to control people’s access to Tahrir Square, and to prevent new mass protests. And in an “imagination taking power”,18 which has sustained the fight to bring down the regime, while supporting the birth of new democratic understanding, the power of the image has been affirmed even in a traditionally abstract and aniconic culture such as Islam.

Arte e Critica, n. 72, October – December 2012, pp. 124-125.

1. In M. Kennard, Global Art Uprising: How the revolutionary spirit transformed creativity, in “The Comment Factory”, 27 February 2012, http://www.thecommentfactory.com/the-global-art-uprising-how-the-revolutionary-spirit-transformed-creativity-6220/

2. See A. Meringolo, I ragazzi di piazza Tahrir, CLUEB, Bologna 2011, pp.83, 92-93; E.Ferrero, Cristiani e musulmani, una sola mano, Emi, Bologna 2012, p.14.

3. See Ferrero, quot., pp.17, 182; Meringolo, quot., pp.57, 101 f.

4. G. C. Argan, “La Storia dell’Arte”, in Storia dell’arte come storia della città, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1993, p. 80.

5. Gene Sharp, From Dictatorship to Democracy. A Conceptual Framework for Liberation, Serpent’s Tail, London 2011.

6. In http://ganzeer.blogspot.com.es/2011/07/free-downloadable-revolutionary-stencil.html#!/2011/07/free-downloadable-revolutionary-stencil.html.

7. In A. C. Madrigal, Egyptian Activists’ Action Plan: Translated, in “The Atlantic”, 27 January 2011, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/01/egyptian-activists-action-plan-translated/70388/

8. On the influence of the Tunisian uprising see W. Ghonim, Revolution 2.0: The power of the people is greater then the people in power: a memoir, it. ed., Rivoluzione 2.0, Rizzoli, Milano 2012, pp. 148-149; Meringolo, quot., pp. 44-45.

9. See ibid., p. 27.

10. J. Jones, Occupy’s V for Vendetta protest mask is a symbol of festive citizenship, in “The Guardian”, 4 November 2011.

11. S. Morayef, For the Love of Graffiti: Cairo’s Walls Trace History of Colourful Revolution, 20 September 2012, in http://suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com/

12. In M. Kennard, Global Art Uprising…, quot.

13. See Meringolo, quot., p.63.

14. See Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, quot.

15. In For the Love of Graffiti…, quot.

16. In his appeal to the artists (in http://streetfiles.org/photos/detail/1240481/) Ganzeer wrote that: “Our only hope right now is to destroy the military council using the weapon of art”.

17. On this subject see Museum for Peace: A contribution to Remembrance, Reconciliation, Art and Peace, Proceedings of the 5th International Peace Museums Conference, Gernika Foundation, Gernika, Spain, 1-7 May 2005.

18. I refer to the slogan of the May 1968 protests, “l’imagination au pouvoir!” or “All power to the imagination!”, inspired to the thought of Herbert Marcuse.